医脉通编译整理,转载请务必注明出处

在过去10年,癌症恶病质领域出现了许多重要的进展,包括对厌食-恶病质综合征(CACS)机制的理解以及有前景的药物和支持治疗手段的发展。昨天医脉通从恶病质和上消化道癌症,以及患者评估两方面进行描述,今日继续更新:

资讯详情》》》癌症厌食-恶病质综合征治疗的现状和未来(上)

目前治疗方法

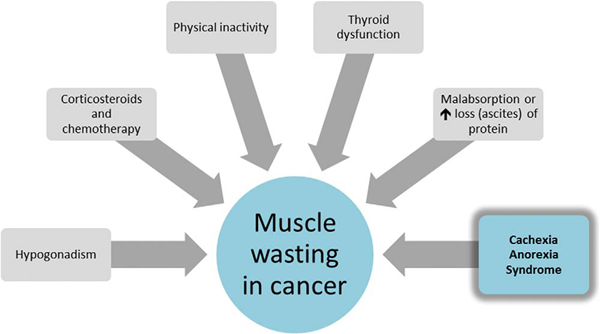

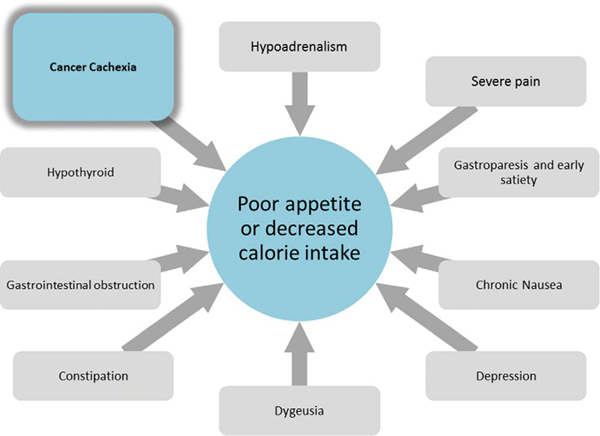

临床评估和治疗应集中于患者的营养状况(摄入量和摄入成分)、引起摄入不良的症状、患者体重和身体组分以及有无可逆的代谢异常(图2、3)。

图2

图3

症状治疗

NIS症状如恶心、抑郁、严重疼痛、味觉障碍、胃瘫和便秘等可CACS患者导致卡路里摄入减少,体重下降(图3)。此外,性腺功能减退、甲状腺功能障碍和维生素B12、维生素D缺乏等代谢异常合并症都可能导致疲劳、肌肉无力和食欲不佳。需要注意其他原因导致的体重下降,如胃肠道梗阻饥饿所致,尤其当这些原因是可逆的,且内镜或手术治疗有效(例如,食管梗阻时行支架放置或内镜扩张)。一项对转诊至某恶病质专科门诊治疗的151名实体瘤患者的回顾性研究发现恶病质患者平均出现3个NIS症状,且15%的患者不低于5个症状[30]。早饱感是最常见的症状。10mg甲氧普胺口服,每4小时1次,可缓解很多患者的早饱症状。进展期癌症患者常有胃瘫和胃动力障碍,甲氧普胺有助于胃容纳更多食物、改善胃动力[31,32]。迟发性运动障碍,尽管罕见,但是一种不可逆的副反应。当治疗超过3个月时,由于用药时间和药物总蓄积量,发生迟发性运动障碍的风险增加,因此应充分权衡治疗获益,决定是否继续使用。便宜易得的药物也可有效控制其他NIS症状。便秘可引起早饱感,使用阿片类或奥坦西隆药物可加剧便秘。尽管鲜有临床研究对比不同泻药的效果,但泻药的确可以有效缓解便秘[33]。抑郁可以减低食欲,抑郁患者应去医师处咨询,若符合适应症应服用抗抑郁药。米氮平和奥氮平是可有效治疗抑郁和恶心的2种药物[34]。一项小规模的米氮平单臂研究显示约有1/4的非抑郁的CACS患者在4周内体重增加了1kg或更多[35,36]。对于味觉障碍,目前无统一有效的治疗,但可尝试硫酸锌[37,38]。有研究表明硫酸锌和屈大麻酚均可以改善化学感受感知,但硫酸锌副作用少。

药物治疗干预

已有药物

孕激素 系统性综述指出甲地孕酮(MA)与安慰剂相比可通过增强食欲和增加体重治疗CACS[39-41]。但是,由于这一阳性结果仅出现在一小部分患者中,且孕激素存在潜在的严重副作用,与其他治疗方式相比未改善生活质量,因此使用孕激素时应权衡利弊[42]。此外,甲地孕酮诱导的体重增加可能主要来自于脂肪或液体,而非肌肉[43]。

2013年更新的Cochrane综述[42]评估了35项临床研究(23项肿瘤相关),共928名消化道肿瘤或胰腺癌患者。约有1/4恶病质患者使用甲地孕酮治疗(例如治疗癌症或艾滋病)后出现食欲改善,1/12的患者体重增加。对3180名患者的用药安全性进行评估。使用甲地孕酮的患者中,尤其是大剂量时,呼吸困难、水肿、尿失禁、血栓栓塞性疾病更加常见,死亡率增加。由于治疗持续中位时间为8周,随访时间短,研究者估计若使用时间更长,不良反应可能会更多。尽管早期研究表明作为次级研究终点的疲劳症状改善[44,45],但有人担忧长时间使用甲地孕酮可能会抑制性腺和肾上腺功能,从而加重疲劳和性欲低下[46]。有症状的肾上腺抑制对于儿童癌症患者问题尤为严重,而对于急症或手术患者建议使用应激剂量皮质激素[47]。由于死亡和血栓栓塞风险增加,患者应被充分告知可能的严重副反应。由于甲地孕酮有抗合成代谢作用,减少肌肉体积,因此应在非常需要增加食欲的患者中使用甲地孕酮[48]。鉴于高剂量甲地孕酮可导致死亡率增加,应该从低剂量起始,并监测效果。虽然体重增加160mg/天时可能食欲改善,但合理的体重增加应超过400mg/天。

糖皮质激素 尽管小规模的临床研究显示糖皮质激素可以改善厌食和疲劳症状,但直到最近2项随机、安慰剂对照的临床研究的开展才证实其疗效[49,50]。进展期癌症患者(主要是头颈部肿瘤和胃肠肿瘤患者)接受每日2次的4mg地塞米松治疗,14天后与安慰剂组相比,疲(P=0.008)和厌食(P=0.013)症状明显改善,而不良反应无明显差别[51]。值得注意的是,生活质量生理方面而非心理方面得到改善。既往一项进展期胃肠肿瘤的研究推测糖皮质激素的作用主要是其改善患者情绪[17]。近期另一项研究对比了连续7天每天2次使用16mg甲泼尼松龙与使用安慰剂的患者,发现疲劳和厌食症状改善,但作为研究主要终点的疼痛强度无差别[52]。尽管研究指出短期使用激素可增强食欲、减少疲劳,但尚无研究证明激素使用有利于瘦组织生成,且长期使用可能导致近端肌病[53]。尽管地塞米松对盐皮质激素影响最小,优于其他激素,其也会引发常见的毒性反应,如念珠菌病、水肿、类库兴样改变、抑郁和焦虑[54]。基于最近的安慰剂对照临床研究结果,结合激素起效快的特点,地塞米松是终末期患者短期使用的最佳选择。

大麻素 大麻素如屈大麻酚和大麻隆被批准用于治疗传统止吐药物无效的化疗相关恶心[55]。屈大麻酚也被批准用于治疗艾滋病患者的厌食症[56],但遗憾的是,鲜有证据表明其对癌症恶病质有效。一项多中心的随机研究纳入了289名进展期癌症患者,以比较大麻提取物δ-9-四氢大麻酚(2.5mg,一天2次)与安慰剂对食欲和生活质量的影响[57]。与其他症状治疗研究一样,研究者观察到了明显的安慰剂效应,三组均食欲改善,且组间无差异(P>0.15)。但患者无服用剂量递增是本研究的一个缺陷。不过此剂量是基于早期的II期研究。该早期研究显示服用高剂量屈大麻酚的患者(5 vs 2.5mg)发生不良精神反应和治疗脱失的风险高[58]。

一项纳入469名患者的多中心随机对照研究比较了甲地孕酮/屈大麻酚联合疗法与单药治疗对肺癌或消化道肿瘤患者的食欲刺激作用[59]。结果显示甲地孕酮优于屈大麻酚,两药联合并无额外获益。尽管既往大型研究结果均为阴性,但近期一项临床随机对照研究显示屈大麻酚可改善味觉障碍癌症患者的味觉,增加蛋白质摄入[60]。

鱼油或二十五碳烯酸 尽管研究表明二十五碳烯酸(EPA)对胰腺癌患者CACS和疲劳有作用[61],但3个系统性综述发现支持EPA治疗癌症恶病质的证据不足[62–64]。虽然未报道严重的不良反应,但腹部不适、嗳气、恶心、腹泻等常影响生活质量。最近2项小规模的随机对照试验显示在非小细胞肺癌患者一线化疗开始后使用鱼油可增加体重和肌肉量,也重燃了研究者们对鱼油的兴趣[65,66]。

沙利度胺 近期一项关于沙利度胺的Cochrane综述发现支持沙利度胺临床应用于癌症恶病质的证据不足[67]。遗憾的是,尽管早期研究发现胰腺癌和食管癌患者使用4周200mg/天的沙利度胺可以提高瘦组织的量且副反应小[68],但综述发表之前的一项关于食道癌患者[70]的研究发现,使用沙利度胺无获益且患者不耐受。近期的一项II期临床试验发现剂量为50mg、100mg时可改善食欲且副作用小[71]。未来可能需要更多的临床试验,但其他研究均遇到了患者招募困难的问题[72]。

参考文献:

[30]Del Fabbro E, Hui D, Dalal S, et al. Clinical outcomes and contributors to weight loss in a cancer cachexia clinic. J Palliat Med. 2011;14:1004-1008.

[31]Shivshanker K, Bennett RW Jr., Haynie TP. Tumor-associated gastroparesis: correction with metoclopramide. Am J Surg. 1983;145:221-225.

[32]Leung J, Silverman W. Diagnostic and therapeutic approach to pancreatic cancer-associated gastroparesis: literature review and our experience. Dig Dis Sci. 2009;54:401-405.

[33]Librach SL, Bouvette M, De Angelis C, et al. Consensus recommendations for the management of constipation in patients with advanced, progressive illness. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2010;40:761-773.

[34]Kast RE, Foley KF. Cancer chemotherapy and cachexia: mirtazapine and olanzapine are 5-HT3 antagonists with good antinausea effects. Eur J Cancer Care (Engl). 2007;16:351-354.

[35]Riechelmann RP, Burman D, Tannock IF, et al. Phase II trial of mirtazapine for cancer-related cachexia and anorexia. Am J Hosp Palliat Care. 2010;27:106-110.

[36]Kim SW, Shin IS, Kim JM, et al. Mirtazapine for severe gastroparesis unresponsive to conventional prokinetic treatment. Psychosomatics. 2006;47:440-442.

[37]Ripamonti C, Zecca E, Brunelli C, et al. A randomized, controlled clinical trial to evaluate the effects of zinc sulfate on cancer patients with taste alterations caused by head and neck irradiation. Cancer. 1998;82:1938-1945.

[38]Halyard MY, Jatoi A, Sloan JA, et al. Does zinc sulfate prevent therapy-induced taste alterations in head and neck cancer patients? Results of phase III double-blind, placebo-controlled trial from the North Central Cancer Treatment Group (N01C4). Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2007;67:1318-1322.

[39]Ruiz-Garcia V, Juan O, Perez Hoyos S, et al. Megestrol acetate: a systematic review usefulness about the weight gain in neoplastic patients with cachexia. Medicina Clinica. 2002;119:166-170.

[40]Pascual Lopez A, Figuls M, Urrutia Cuchi G, et al. Systematic review of megestrol acetate in the treatment of anorexia-cachexia syndrome. J Pain Symptom Manag. 2004;27:360-369.

[41]Lesniak W, Bala M, Jaeschke R, et al. Effects of megestrol acetate in patients with cancer anorexia-cachexia syndrome-a systematic review and meta-analysis. Polskie Archiwum Medycyny Wewnêtrznej. 2008;118:636-644.

[42]Ruiz Garcia V, Lopez-Briz E, Carbonell Sanchis R, et al. Megestrol acetate for treatment of anorexia-cachexia syndrome. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013;3:CD004310.

[43]Lambert CP, Sullivan DH, Freeling SA, et al. Effects of testosterone replacement and/or resistance exercise on the composition of megestrol acetate stimulated weight gain in elderly men: a randomized controlled trial. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2002;87:2100-2106.

[44]Bruera E, Macmillan K, Kuehn N, et al. A controlled trial of megestrol acetate on appetite, caloric intake, nutritional status, and other symptoms in patients with advanced cancer. Cancer. 1990;66:1279-1282.

[45]Simons JP, Aaronson NK, Vansteenkiste JF, et al. Effects of medroxyprogesterone acetate on appetite, weight, and quality of life in advanced-stage nonhormone-sensitive cancer: a placebo-controlled multicenter study. J Clin Oncol. 1996;14:1077-1084.

[46]Dev R, Del Fabbro E, Bruera E. Megestrol acetate treatment associated with symptomatic adrenal insufficiency and hypogonadism in male patients with cancer. Cancer. 2007;110:1173-1177.

[47]Orme LM, Bond JD, Humphrey MS, et al. Megestrol acetate in pediatric oncology patients may lead to severe, symptomatic adrenal suppression. Cancer. 2003;98:397-405.

[48]Evans WJ. Editorial. Megestrol acetate use for weight gain should be carefully considered. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2007;92:420-421.

[49]Bruera E, Roca E, Cedaro L, et al. Action of oral methylprednisolone in terminal cancer patients: a prospective randomized double-blind study. Cancer Treat Rep. 1985;69:751-754.

[50]Moertel CG, Schutt AJ, Reitemeier RJ, et al. Corticosteroid therapy of preterminal gastrointestinal cancer. Cancer. 1974;33:1607-1609.

[51]Yennurajalingam S, Frisbee-Hume S, Palmer JL, et al. Reduction of cancer-related fatigue with dexamethasone: a double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled trial in patients with advanced cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2013;31:3076-3082.

[52]Paulsen Ø, Klepstad P, Rosland JH, et al. Efficacy of methylprednisolone on pain, fatigue, and appetite loss in patients with advanced cancer using opioids: a randomized, placebo-controlled double-blind trial. J Clin Oncol. 2014;32:3221-3228.

[53]Batchelor TT, Taylor LP, Thaler HT, et al. Steroid myopathy in cancer patients. Neurology. 1997;48:1234-1238.

[54]Sturdza A, Millar B-A, Bana N, et al. The use and toxicity of steroids in the management of patients with brain metastases. Support Care Cancer. 2008;16:1041-1048.

[55]Poster DS, Penta JS, Bruno S, et al. delta 9-tetrahydrocannabinol in clinical oncology. JAMA. 1981;245:2047-2051.

[56]Beal JE, Olson R, Laubenstein L, et al. Dronabinol as a treatment for anorexia with weight loss in patients with AIDS. J Pain Symptom Manage. 1995;10:89-97.

[57]Strasser, F, Luftner, D, Possinger, K, et al. Comparison of orally administered cannabis extract and delta-9-tetrahydrocannabinol in treating patients with cancer-related anorexia-cachexia syndrome: a multicenter, phase III, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled. J Clin Oncol. 2008;24:3394.

[58]Plasse TF, Gorter RW, Krasnow SH, et al. Recent clinical experience with dronabinol. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 1991;40:695-700.

[59]Jatoi A, Windschitl HE, Loprinzi CL, et al. Dronabinol versus megestrol acetate versus combination therapy for cancer-associated anorexia: a North Central Cancer Treatment Group study. J Clin Oncol. 2002;20:567-573.

[60]Brisbois TD, de Kock IH, Watanabe SM, et al. Delta-9-tetrahydrocannabinol may palliate altered chemosensory perception in cancer patients: results of a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled pilot trial. Ann Oncol. 2011;22:2086-2093.

[61]Fearon KC, Von Meyenfeldt MF, Moses AG, et al. Effect of a protein and energy dense N-3 fatty acid enriched oral supplement on loss of weight and lean tissue in cancer cachexia: a randomised double blind trial. Gut. 2003;52:1479-1486.

[62]Dewey A, Baughan C, Dean T, et al. Eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA, an omega-3 fatty acid from fish oils) for the treatment of cancer cachexia. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2007;1:CD004597.

[63]Ries A, Trottenberg P, Elsner F, et al. A systematic review on the role of fish oil for the treatment of cachexia in advanced cancer: an EPCRC cachexia guidelines project. Palliat Med. 2012;26:294-304.

[64]Mazzotta P, Jeney CM. Anorexia-cachexia syndrome: a systematic review of the role of dietary polyunsaturated fatty acids in the management of symptoms, survival, and quality of life. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2009;37:1069-1077.

[65]Murphy RA, Mourtzakis M, Chu QS, et al. Nutritional intervention with fish oil provides a benefit over standard of care for weight and skeletal muscle mass in patients with nonsmall cell lung cancer receiving chemotherapy. Cancer. 2011;117:1775-1782.

[66]van der Meij BS, Langius JA, Spreeuwenberg MD, et al. Oral nutritional supplements containing n-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids affect quality of life and functional status in lung cancer patients during multimodality treatment: an RCT. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2012;66:399-404.

[67]Reid J, Mills M, Cantwell M, et al. Thalidomide for managing cancer cachexia. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012;4:CD008664.

[68]Wilkes EA, Selby AL, Cole AT, et al. Poor tolerability of thalidomide in end-stage oesophageal cancer. Eur J Cancer Care. 2011;20:593-600.

[69]Gordon JN, Trebble TM, Ellis RD, et al. Thalidomide in the treatment of cancer cachexia: a randomized placebo controlled trial. Gut. 2005;54:540-545.

[70]Khan Z H, Simpson EJ, Cole AT, et al. Oesophageal cancer and cachexia: the effect of short-term treatment with thalidomide on weight loss and lean body mass. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2003;17,677-682.

[71]Davis M, Lasheen W, Walsh D, et al. A phase II dose titration study of thalidomide for cancer-associated anorexia. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2012;43:78-86.

[72]Yennurajalingam S, Willey JS, Palmer JL, et al. The role of thalidomide and placebo for the treatment of cancer-related anorexia-cachexia symptoms: results of a double-blind placebo-controlled randomized study. J Palliat Med. 2012;15:1059-1064.

未完,待续。。。。。。

医脉通编译自:Current and Future Care of Patients with the Cancer Anorexia-Cachexia Syndrome,2015 ASCO Educational Book